On March 25, 2025, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued the "Statement on Certain Proof-of-Work Mining Activities". The statement indicates that obtaining crypto asset rewards through participating in a PoW consensus mechanism by providing computational power on a permissionless public blockchain does not constitute a securities issuance as defined by securities law. Although this statement lacks direct legal force, its legal quality marks a significant progress in the SEC's regulatory approach to digital assets.

This change coincides with a comprehensive overhaul the U.S. crypto regulatory framework. Since the Trump administration promoted an inclusive regulatory framework for the crypto industry, U.S. crypto policies have experienced a phase of "enforcement-driven priority." Between 2021 and 2023, the SEC initiated intensive enforcement actions against multiple centralized platforms and ICO projects. Since 2023, as regulatory agencies have gradually clarified the boundary between "securities-based tokens" and "non-securities-based native assets," the policy orientation has shifted from "comprehensive suppression" to "categorized guidance and explicit exemptions."

This statement on PoW protocol mining emerged under this trend, providing clear compliance guidance for participants in mining activities, mining pool operators, and the entire PoW ecosystem. This report will systematically analyze the policy implications, trace the evolution of crypto asset securities qualification, and highlight the statement's impact on crypto asset taxation and other areas.

The SEC's statement, issued by its Division of Corporation Finance, addresses whether certain mining activities on open and permissionless PoW networks constitute the offer and sale of securities under Section 2(a)(1) of the Securities Act of 1933 and Section 3(a)(10) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. It clarifies that specific mining activities, particularly those involving hash power contribution to consensus mechanisms and protocol-level reward acquisition, do not fall within the scope of securities issuance. Specifically, two categories of activities are exempted:

·Self/Solo Mining: Miners utilize their own computational resources to participate in transaction verification and block generation on PoW networks, directly receiving crypto asset rewards from the protocol.

·Mining Pool: Multiple miners combine their hash power for joint mining. A pool operator coordinates work distribution and reward allocation, with rewards shared proportionally to hash power contributions. Even when managed by an operator, the essence of such activities remains unaffected, as long as the operator’s role remains “administrative” or “ministerial”.

The statement further explains that these "protocol mining activities" do not meet the Howey test standards applied by the SEC, particularly failing to satisfy the key element of "profits derived from the efforts of others." Miners earn rewards by supplying computational resources and adhering to technical protocols, representing active participation and labor rather than passive gains reliant on third-party operational capabilities.

This statement confirms that rewards obtained by miners or mining pools through solo or pool mining on PoW networks do not qualify as securities and are not regulated by securities law.

To understand this statement, it is essential to grasp the following three core principles:

·Limited Law Effect, Clear Policy Signal

As an official position of the SEC's Division of Corporation Finance, the statement lacks law effect but reflects the regulatory authorities' enforcement attitude and policy orientation in specific areas, offering substantial market guidance.

·Substantive Risk Exclusion, Explicit Exemption Applicability

By excluding the securities attributes of specific PoW protocol mining activities, the statement delineates a clear "compliance boundary," aiding miners, pool operators, and platforms in identifying which on-chain activities do not constitute the offer and sale of securities, thereby reducing potential legal risks.

·Clear Understanding, Strict Applicability Conditions

The statement applies only to mining activities on permissionless PoW networks where computational power is provided to participate in consensus mechanisms. The miner should only engage in an administrative or ministerial activity Any mining projects beyond this scope, involving fundraising or investment promises may still be subject to securities regulation.

Under the SEC's non-securitization framework for PoW mining activities, Kaspa stands out as a quintessential protocol public chain project that aligns with the SEC's exemption rationale. The project has never engaged in any form of pre-mining, presale, or team reservations. Instead, it relies on the PoW mechanism to drive its fully open network operations, with token allocation entirely dependent on mining activities controlled by the protocol. Miners participate in consensus through computational power and automatically receive block rewards according to the protocol's algorithm, without any reliance on the operational efforts of a development team. The acquisition of tokens in Kaspa meets the criteria described by the SEC as indicative of non-securities behavior under protocol-level PoW systems..

Furthermore, as the world's first Layer-1 PoW chain adopting the BlockDAG (Directed Acyclic Graph) structure, Kaspa's official website showcases its unprecedented vision and technological advantages. Kaspa positions itself as the "fastest, open-source, decentralized, and scalable" blockchain globally, supporting parallel block processing and instant confirmation while maintaining network security backed by PoW. Its technical implementation enables second-level block times and extremely high throughput without resorting to centralized ordering or compromising on-chain data integrity. In terms of project communication, Kaspa emphasizes protocol operations, open participation, and on-chain expansion capabilities rather than investment returns, token appreciation, or financial expectations on its homepage, fully reflecting a "human-centric" and "protocol-first" project positioning.

From the perspective of both the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), not all crypto tokens are securities under the current legal framework. However, regulatory agencies retain the authority to classify specific crypto assets as securities based on their characteristics and structures.

Starting with U.S. securities legislation, this paper summarizes the evolution of cryptocurrency securities qualification by incorporating practical cases:

U.S. Securities Legislation

U.S. securities legislation exemplifies a typical legislative model distinguishing between securities issuance and trading regulations. The Securities Act of 1933 primarily governs securities issuance, while the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 focuses on securities trading. The definition of securities is outlined in Section 2(a)(1) of the 1933 Securities Act: Securities refer to any notes, stocks, treasury stocks, security futures, security-based swaps, bonds, debts, debt instruments, profit-sharing certificates, or interests in any profit-sharing agreements… or any interests or instruments commonly known as "securities," or any certificates, temporary or interim certificates, receipts, guarantees, or subscription or purchase rights for the aforementioned items.

Analysis reveals that securities under U.S. law can be categorized into three types:

·Clearly defined securities: stocks, notes, bonds, options, etc.

·Instruments specific to certain economic sectors: mineral rights, oil and gas interests, etc.

·Investment contracts: a catch-all provision, with the determination of whether an investment contract qualifies as a security left to judicial interpretation.

The SEC, established under the 1934 Securities Exchange Act as an independent agency and quasi-judicial body of the U.S. federal government, is the highest supervisory authority for the U.S. securities industry. Its primary responsibilities include protecting investors, maintaining fair, orderly, and efficient markets, and promoting capital formation. It achieves these goals through rule-making, law enforcement, and oversight of securities market participants.

The catch-all provision grants the SEC broad interpretive discretion, allowing it to adapt to emerging financial instruments through purposeful and substantive analysis. This provision nearly a century later also helps with judicial determinations of cryptocurrency securities status.

Cryptocurrencies and related activities have long been subjected to securities regulation, even when their profit models do not resemble traditional securities. This is attributed to the following four reasons:

·The SEC's Long-Standing Conservative Regulatory Strategy

The SEC bears the responsibility of protecting interests’ of investors in the crypto asset space with a "broad regulatory" approach: it prefers to "include first, assess later" rather than grant exemptions readily, particularly when crypto assets involve monetary flows and investor profit expectations. The SEC often prioritizes the Howey test to determine whether they constitute securities.

·The Howey Test Allows for Interpretive Flexibility

Originating from the 1946 Supreme Court case SEC v. Howey, the Howey test is used to determine whether a transaction falls with the “investment contract” under U.S. securities law. It requires meeting the following four criteria to be considered a security: (1) an investment of money; (2) in a common enterprise; (3) with an expectation of profits; and (4) derived primarily from the efforts of others. Certain mining activities may constitute investment contracts, especially the "shared profit" mechanism in Mining Pool.

·The Ambiguous Boundaries of "Fringe Scenarios" Such as Mining Pool, Cloud Mining, and Hosted Mining

The market has seen numerous projects like "cloud hashing power" "hosted mining",and "mining equipment leasing": investors solely provide funds, while the fundraisers handle the purchase of mining equipment and operation of the devices, with investors receiving mining rewards periodically. The structure of these projects closely resembles securities, with profits reliant on the operational efforts of the project party. With a proliferation of such models, the SEC may not discern every form of mining and thus, adhering to legal prudence, maintains a uniform ambiguous stance: crypto mining carries high risks and cannot be ruled out as possessing securities attributes.

·Regulatory Practices Lag Behind Technological and Organizational Evolution

The SEC regulates emerging technologies under traditional legal frameworks such asthe Securities Acts of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, despite the significant differences between the two domains. Early crypto-industry chaos (frauds, and scams) necessitated comprehensive regulation to maintain industry stability andinvestor protection.

In summary, as the regulatory framework for cryptocurrencies continues to evolve, regulatory agencies are gradually clarifying the legal boundaries of various on-chain activities. This statement represents a step in that direction, laying the groundwork for a clearer and more predictable compliance environment. We anticipate that the investment and participation landscape for crypto assets will continue to improve in transparency and orderliness.

Evolution Path

Starting from Section 2(a)(1) of the Securities Act of 1933 and incorporating the evolution of Howey test case law, this paper outlines the theoretical basis for why crypto assets and related activities may be subject to securities regulation. The following points can be summarized:

·Securities law serves as the core, with investment contracts acting as a catch-all provision to address emerging financial formats;

·The Howey test is the primary tool for application, with its four elements serving as universal criteria for determining whether an "investment contract" exists;

·The token's name and intended purpose are not exempting factors; the determination hinges on investors' expectations and its operational framework. Projects characterized by heightened complexity and reduced decentralization face greater likelihood of being classified as securities. Emerging models such as mining pools, staking mechanisms, and lending protocols are increasingly being brought within the regulatory scope of 'quasi-securities conduct'.

·The SEC's regulatory strategy is becoming more cautious, characterized by "broad application + case-specific qualification".Its regulatory stance is shifting from ambiguity to risk-oriented and context-specific assessments.

On this legal foundation, we can more clearly review the SEC's regulatory practices regarding crypto asset securities qualification in recent years. By analyzing several landmark cases, we observe a "gradual evolution path" in the SEC's regulatory strategy, moving from initial exploration and broad application to scenario-specific differentiation and the introduction of decentralization and investor type factors for context-specific assessments.

The following outlines the key evolutionary journey of crypto asset securities qualification through actual cases.

·SEC v. Trendon Shavers Case (2013): The First Case Involving Bitcoin Securities Fraud

In 2013, the SEC sued Trendon Shavers for operating the "Bitcoin Savings and Trust" (BST) project, alleging securities fraud. This marked the first SEC enforcement action involving Bitcoin in U.S. history. The court ultimately upheld the SEC's position, ruling that the Bitcoin investment scheme constituted a securities offering.

BST positioned itself as a "high-yield Bitcoin investment plan," with Shavers soliciting Bitcoin from the public and promising a fixed weekly return of 1%. He claimed that the Bitcoin would be used for arbitrage trading to generate profits, with investors receiving dividends weekly. The project absorbed over 700,000 BTC, but later suffered a broken capital chain, causing significant losses to numerous investors.

On September 18, 2014, the U.S. District Court for the Sherman, Texas, entered a final judgment against Trendon T. Shavers and BST. Shavers had established this online entity to perpetrate a Ponzi scheme, defrauding investors of over 700,000 bitcoins. The court ordered Shavers and BST to disgorge over $40 million in ill-gotten gains and prejudgment interest and required each defendant to pay a $150,000 civil penalty.

The SEC contended that although the investment asset was Bitcoin, the transaction essentially constituted an "investment contract" and thus fell within the scope of securities law. The court determined that investors contributed assets (BTC); the funds were pooled under Shavers' unified management; investors expected profits; and the returns were derived from Shavers' trading activities (efforts of others). This case, while not involving "tokens" or "on-chain projects," clearly signaled the SEC's stance: "Even if the investment asset is Bitcoin, securities law applicability cannot be exempted; the key lies in the financing structure and profit logic."

·The DAO Case (2017): Cryptocurrency's First Recognition as a Security by the SEC

In 2017, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued an investigative report on The DAO project, explicitly stating that tokens named "DAO" qualified as "securities" and should be subject to securities regulation. Although the SEC did not initiate enforcement action against the project team, the report sent shockwaves through the industry and marked the SEC's entry into crypto asset regulation.

The DAO was a "decentralized autonomous organization" operating on Ethereum, which raised over $150 million in ETH through a "crowdfunding" model to invest in future projects proposed and screened by the community. In essence, it functioned as an on-chain "venture capital platform."

The SEC, invoking the Howey test, concluded that the DAO's offerings constituted an "investment contract": investors contributed funds (ETH), pooled in a shared platform (The DAO) for operation, expecting profits from project investments managed by curators and project teams. Despite The DAO's claims of "decentralized governance," the SEC found that actual control remained with specific technical personnel and curators, with investors lacking genuine operational control over the projects. This case established the regulatory logic that "crypto tokens may qualify as securities."

· Munchee Case (2017): Utility Tokens Don’t Automatically Qualify as Compliant Items

Munchee, a food review app platform, planned to issue MUN tokens in 2017 for in-app rewards and user incentives. The SEC swiftly intervened and halted the ICO, determining that the token offering constituted a securities transaction.

Munchee claimed that MUN was a "utility token" usable for internal payments and incentives within the app, lacking investment attributes. However, the project extensively promoted the tokens' appreciation potential and investment returns through social media and marketing materials, attracting numerous speculative investors.

The SEC argued that despite MUN's technical "utility," the project's promotions fostered investment expectations among users, a critical component of the Howey test. Investors purchased MUN not for consumption or usage but for capital appreciation as the platform grew, user base expanded, and scarcity increased. Additionally, the project's operations relied entirely on the Munchee team's efforts, making the investment reliant on the team's managerial capabilities and thus qualifying as an "investment contract." The SEC emphasized that even with technical functionalities, projects with evident financing logic and profit expectations may still be classified as securities.

·BitClub Network Case (2019): Illegal Securities and Fraud under the Guise of "Cloud Mining"

In December 2019, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), in collaboration with the IRS, announced the dismantling of the global crypto-mining investment project known as "BitClub Network." Since 2014, the project had raised over $700 million from investors worldwide under the pretext of "hash power sharing," later uncovered as a Ponzi scheme. Key individuals faced criminal charges, including securities fraud, wire fraud, and money laundering.

BitClub Network purported to offer "cloud mining" services, where investors could purchase mining rig shares or hash power contracts, with the platform promising regular dividends based on mining revenues. The project targeted retail investors, operated without regulatory approval, and failed to disclose its actual hash power status. The funds, after flowing to the project team, were largely not used for actual mining activities but instead were directed toward paying early investors and weremisappropriated.

Although led by the DOJ, the case's core legal violations were closely tied to securities law. BitClub Network promised investors stable mining returns, requiring only capital investment without participation in actual mining operations. Profits were entirely dependent on the platform's "mining activities," satisfying all four elements of the Howey test: (1) investment of money; (2) in a common "mining pool"; (3) with an expectation of profits; and (4) derived solely from the efforts of the project party.

Furthermore, the project's promotional materials, distribution system, and fund management bore striking similarities to illegal fundraising and securities fraud. Ultimately, this case was handled as one of the few crypto-related criminal "mining fraud securities cases," serving as a powerful deterrent.

·Ripple Labs Case (2020–2025): The Gray Area of Securities Qualification

In 2020, the SEC initiated litigation against Ripple Labs, alleging that Ripple's continuous sale of XRP to the public constituted an unregistered securities offering. This case became one of the most controversial and influential crypto lawsuits in U.S. history. In 2023, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York issued a split decision that marked a pivotal moment in digital asset regulation: it held that Ripple’s XRP sales to institutional investors qualified as securities, while programmatic sales to retail investors on digital asset exchanges did not.

Ripple, a company offering cross-border payment solutions, had long raised operational funds by selling XRP to both institutions and the broader public. The SEC claimed these sales constituted investment contracts under the Howey test, as investors allegedly expected profits based on Ripple’s efforts to develop the XRP ecosystem.

The court agreed in part. It ruled that institutional buyers had a reasonable expectation of profit derived from Ripple’s efforts—meeting all prongs of the Howey test. In contrast, for programmatic buyers on secondary markets, the court found that the third prong—“expectation of profits”—was not satisfied, due to the economic realities of how such transactions occurred. As stated in the opinion:

“Having considered the economic reality of the Programmatic Sales, the Court concludes that the undisputed record does not establish the third Howey prong.”

“Programmatic Buyers could not reasonably expect the same [profits],” because these blind bid/ask transactions made it unclear whether funds went to Ripple at all (Case No. 1:20-cv-10832-AT-SN, Document 874, p.23).

This context-specific reasoning—considering who the investor is and how the transaction occurred—marks a shift away from the SEC’s historically broad approach toward crypto offerings. It affirms that not all sales of a digital asset automatically constitute securities transactions.

Following the SEC’s appeal, months of litigation ensued. In May 8th, 2025, as stated in the SEC’s Litigation Release No. 26306, Ripple and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had reached a settlement agreement. Ripple agreed to pay $50 million of the original $125 million civil penalty, with the remaining $75 million refunded to the company. Both parties agreed not to pursue further appeals or seek to overturn the prior judgment.

·BlockFi Case (2022): Structured Crypto Financial Products Trigger Securities Regulation

In 2022, the SEC took enforcement action against crypto financial platform BlockFi, alleging that its "BlockFi Interest Account" (BIA) effectively constituted an unregistered securities product. BlockFi ultimately settled with the SEC, paying a $100 million fine and restructuring its business.

BlockFi offered a crypto deposit product where users could deposit Bitcoin, Ethereum, and other crypto assets to earn annual returns. BlockFi committed to using these assets for loans or investments, with generated returns passed back to users. Although the platform did not issue crypto tokens, the product effectively formed a "lending agreement" structure.

The SEC determined that BIA accounts qualified as "investment contracts" under the Howey test. Users deposited crypto assets, pooled for unified platform management, without direct involvement in operations. Instead, users relied on BlockFi to generate profits through reinvestment and expected returns. While not a traditional securities issuance, the product's revenue structure, beneficiary logic, and operational model bore strong similarities to securities. This case clarified that even crypto products not involving token issuance could constitute securities if they met the elements of an investment contract.

·ETH ETF Regulatory Controversy (2024): The Compliance Shift of Decentralized Assets

In 2024, the market witnessed strong momentum for the launch of Ethereum spot ETFs, reigniting discussions within regulatory circles on whether Ethereum (ETH) qualifies as a security. Although no formal ruling emerged, the SEC demonstrated a growing inclination to classify ETH as a "commodity" rather than a security.

As the second-largest crypto asset globally, ETH, since its inception in 2015, has gradually decentralized its network, transitioning from Proof-of-Work (PoW) to Proof-of-Stake (PoS), with its technical and governance structures increasingly resembling native financial infrastructure. Post-2023, the SEC's regulatory stance on ETH has softened, while the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has consistently regarded it as a "commodity."

Although Ethereum's initial token issuance via fundraising exhibited certain securities characteristics, over time, its operation has become independent of any centralized organization, with no clear entity driving its value growth. The SEC has gradually accepted that "decentralization" is key to mitigating the "efforts of others" criterion under the Howey test. During the ETF review process, the SEC did not classify ETH as a security nor obstruct the issuance of its derivatives. This case indicates that decentralization will become a pivotal criterion in determining the securities status of native on-chain assets.

Through the above analysis of seven typical cases, we can observe how U.S. regulatory agencies have gradually built a practical framework for determining the securities qualification of crypto assets across different stages, asset types, and regulatory outcomes. These cases reflect the SEC's interpretation of securities law and indicate a shift in regulatory focus from "whether it is a token" to "whether it possesses the attributes of an investment contract."

Figure 1 below systematically outlines the evolution of crypto asset securities qualification, including phase summaries, typical cases, and relevant regulations.

Since Bitcoin was first brought into the regulatory spotlight in 2013, the securities qualification path of U.S. crypto assets has gone through four key stages: experimentation with traditional laws, systematic law enforcement, categorized regulation, and refined exemptions. Over the past decade-plus period, regulatory agencies have progressively established a substantive assessment framework based on investment contract determination (Howey) through landmark case rulings and policy statements. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin have largely been excluded from the securities definition due to their key feature of decentralization.

The representative regulations and cases across different years reflect the evolution of regulatory tools from ambiguity to clarity and reveal the SEC's stance on "whether crypto assets are securities" transitioning from "broad applicability" to "risk-based and context-specific assessment." From 2024 to 2025, with the implementation of Trump's crypto-friendly policies, areas such as ETH and PoW mining have been explicitly excluded from securities regulation. Future regulatory trends are moving toward standardized rules and clear boundaries.

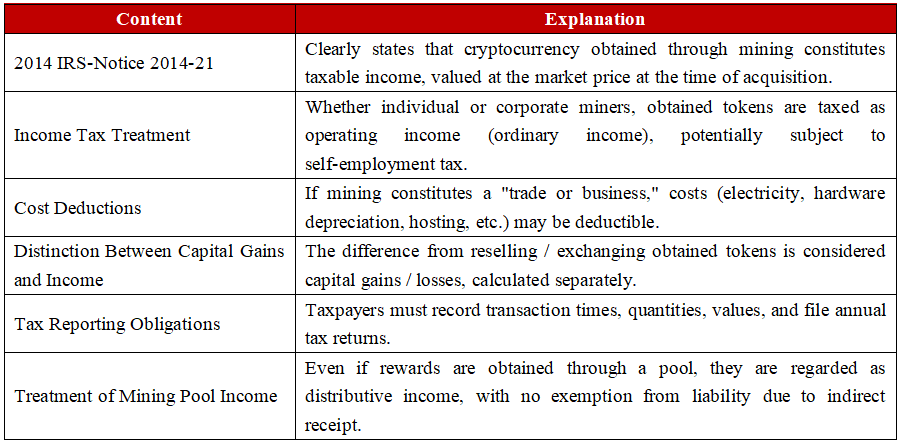

Despite the SEC's exclusion of "protocol-level mining activities" from the definition of securities in its statement -providing miners and pool operators with clear compliance boundaries - this does not imply that mining activities are exempt from tax obligations.

The SEC regulates securities, while tax regulation falls under the IRS, which operates on different assessment logic and enforcement objectives. The IRS has never regarded mining income as "securities investment income." As early as 2014, the IRS clarified that "crypto mining rewards" should be treated as taxable income and included in total income at their "fair market value at the time of receipt." Capital gains from subsequent sales must also be taxed (short-term or long-term). Thus, even though the statement absolves mining activities of securities attributes, miners still bear tax reporting obligations upon receiving mining rewards.

From a practical standpoint, this implies:

·All obtained tokens from solo or pool mining must be declared as income.

·Miners need to calculate the USD value of the tokens at the time of acquisition and declare it during annual tax filing.

·Cost expenditures (electricity, equipment, etc.) may be deductible but must meet IRS-specified operational standards.

It is important to note that since this statement confirms that mining activities are not securities issuances, it also eliminates any potential pathways for evading reporting obligations through securities exemptions. Tax liabilities now fall more directly and independently on miners or pool operators themselves. While this statement alleviates miners' concerns at the securities law level, it also means they must strictly fulfill their tax reporting obligations related to the IRS. In the context of increasingly refined compliance standards, being classified as "non-securities" does not equate to "no liability," rather, it requires miners to reassess their tax obligations and associated risks.

In summary, the SEC's recent statement on PoW mining, while not legislative in nature, serves as a crucial milestone in the evolution of regulatory logic. It signals that the U.S. regulatory environment is gradually accepting that "native on-chain behaviors" are not inherently fall within the scope of securities regulation. The market is progressing toward a "more transparent, rule-based, and predictable" compliance landscape. Amid this trend, all stakeholders — miners, platforms, developers, and investors — should focus on aligning structural design, operational positioning, and information disclosure with compliance pathways.